Here's a review of

Strange Tribe that came out on the Ohio State University newspaper, the Lantern, the day before my lecture.

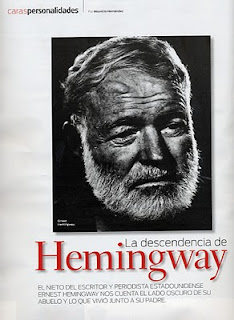

Hemingway's grandson to bring troubled family tree to Wex through his memoir

Amanda Bishop

For John Hemingway, having a famous last name wasn't so much a gift as a package deal. Along with that name came a schizophrenic mother, a transvestite father, and a grandfather who, though a brilliant wordsmith, was also a manic-depressive who killed himself.

Hemingway, a writer and translator who lives in Montreal with his wife and two children, will appear at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 17 at the Wexner Center Film and Video Center to talk about his aptly-named memoir, "Strange Tribe." The appearance and book-signing, sponsored by the Department of English and the Sexuality Studies program, is free and open to the public.

John HemingwayThe memoir represents a son's effort to forgive, to deal with ghosts of his own and help people to understand the troubles and secrets that sifted down through generations of the Ernest Hemingway clan.

"The hardest thing was seeing what happened to them. I wanted to help them, but there was nothing I could do," said Hemingway, in a telephone interview. "It's difficult when you have all that pain wrapped up. How are you going to deal with that? I was thinking, 'I've had enough of that. It's not my problem.' But it is."

His father, Gregory Hemingway, was the youngest of Ernest Hemingway's three sons. The other two boys were blond; Gregory had the dark hair of his mother, Hemingway's second wife, Pauline. Ernest called him by a nickname, "Gigi," took him out shooting, and was proud of his marksmanship.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JOHN HEMINGWAY

From Left: Patrick, Jack, Ernest and Gregory Hemingway pose together. Ernest' grandson, John Hemingway will appear at the Wexner Film and Video Center on Feb. 17 to discuss his recent memoir, 'Strange Tribe.'But like Ernest, Gregory would suffer from both bi-polar disorder and a drinking problem. He also had a fixation with cross-dressing that began in boyhood. Gregory underwent a series of sexual reassignment surgeries as a man, and eventually took the name of "Gloria."

Gregory Hemingway had too many issues of his own to be a reliable father, so John, who did not inherit his father's manic depression, spent much of his childhood living in Miami with Ernest's brother, Leicester. For years, John alternated between anger at his father and a longing to reconnect with him. He decided to write the memoir after his father's death in Miami in 2001 at the age of 69.

One of the most poignant passages in the memoir is John's recollection about going to the movies with his father. It was a tradition he enjoyed, one of the rare father-son bonding experiences salvaged from a sporadic relationship. Near the end of one of the films, the two of them watched as a troubled character on the screen sat in an office with a gun, put it to his head and pulled the trigger.

At the sound of the shot, Gregory crumpled in his seat, rocking, moaning: "No, no, oh, no." John knew immediately why his father was reacting so strongly: in 1961, Ernest Hemingway, paranoid, depressed, unable to write and in failing health, had committed suicide in similar fashion.

Four Hemingway family members, besides Ernest, committed suicide - his father, sister, brother, and a granddaughter.

In researching the memoir, poring through old family letters and consulting with a new wave of Hemingway biographers, John Hemingway was struck by the similarities between Ernest and Gregory.

"Both were very witty and funny. They could also hold grudges. If you got on their bad side it would take you awhile to get back on their good side," he said. "Both of them were bipolar, and had a lifelong battle to achieve a balance between male and female."

That balancing act, on Ernest Hemingway's part, has been a hot topic among Hemingway scholars since the publication, in 1986, of an unfinished Hemingway manuscript that was stitched into a novel entitled "The Garden of Eden."

In the novel, the main characters, David and Catherine, engaged in sexual role playing in which they get identical haircuts and reverse gender roles in bed: At one point Catherine tells David "Now kiss me and be my girl." Hemingway scholars such as Carl Eby at the University of South Carolina and Debra Moddlemog of Ohio State have written extensively about the roots of Hemingway's fascination with such experimentation, which may reflect a little-known side of the two-fisted writer and macho adventurer.

John Hemingway theorizes that Ernest Hemingway's fascination with his own feminine side softened his attitude toward his gender-bending son. As evidence, he offered a story Gregory told him. It is a story that would ultimately give John Hemingway two gifts: a title for his memoir, and a heightened understanding of the relationship between his troubled father and his world-famous grandfather.

"I think that my dad was around 11 or 12, and he had put on a pair of his mother's nylons," John remembered. "Ernest walked into the room, stared at him for a moment, shocked, then walked out again without saying a word. But a few days later, he looked at Gregory and said: 'Gigi, you and I come from a strange tribe.' "