Here's a short story of mine that was published in the Spring 2010 edition of

Saw Palm, the Florida Literature and Art journal of the University of South Florida.

Miami Sunrise

Brylcreem Man

When he looked at himself in the mirror his long, black, wiry hair was as it had been the night before, disheveled and with a sheen that could have been mistaken for Brylcreem. His eyesight had never been that good and when he found his glasses he noticed the white roots and made a mental note to pick up a box of hair color. His girlfriend was still in bed and if he could find a pharmacy that was open he’d have everything done before she got up, but he was tired and feeling stressed and went for a walk on the beach instead.

What he really needed was a vacation and not just a break from the city. Flying down to Miami and staying at the hotel where he and his mother had always stayed when she was alive helped, but it couldn’t make up for the lack of sleep nor the state of his career. Mentiroso was now a has-been in the world of avant-garde theater. He had come to a dead end, and for the past six months he’d been forced to pay his bills either in cash or with his girlfriend’s credit card. Times were bad but this lack of work was something that he had never experienced before. It was positively plebian, lower class and demeaning, and he wondered how much longer he would have to hand deliver the $2,000 of his monthly rent in crisp $100 dollar bills.

“Was any of this my fault?” he asked himself rhetorically as he stepped out of the elevator and walked towards the pool and the beach beyond it. Could he be blamed for stating the truth about that hotel in Rome? Should he have said nothing of the raw sewage smell from the toilet?

“Was that my fucking fault?!” he said out loud as he brushed past a Guatemalan maid and a Venezuelan pool cleaner. He hadn’t planned on broadcasting the filth of his lodgings to the rest of Italy but how was he supposed to know that one of the journalists that he’d spoken to would actually print what he had to say?

That was where he’d screwed himself. The paper published his “defamatory statements” and the next thing he knew the hotel was suing him. “Mentiroso dice che la sua stanza fa schifo” (Mentiroso says that his room sucks) was the title that the newspaper ran and it was more than enough. He had a reputation for trash talk and over the years he’d made many enemies on both sides of the Atlantic, but in spite of everything his talent (which was real) had always protected him. He’d been sued before, but this time it was different. After the stock market crash people weren’t as forgiving as they used to be. If in the past a judge might have seen him as a kind of clown and let him off with a slap on the wrist, tolerance was now a rare commodity and you had to be careful. For the hotel owners he was an easy mark and the lawyer’s fees and the fine wiped out the million in stocks and gold that he’d saved.

When he opened the gate to the beach he took his shoes off so that he could feel the sand on his feet. In New England there was a foot of snow on the ground but here it never got cold. His mother liked to compare it to the town in southern Italy where she’d been raised. “Feel how fine the sand is,” she would say, “and look at the clear blue of the water and you’ll know what it was like for me when I was your age.” The water, of course, was still blue but it had never revealed much to him about his mother’s upbringing. She had serious issues with the truth and could invent the most outrageous stories. When he was a boy she would often tell him that his father was a black American G.I. who she’d met after the war and that that was the reason for his kinky hair, or that the Mentirosos were Italian nobility but that they’d lost everything during the Fascist years. None of it was true, or perhaps all of it was, who could really say? When someone was lying to you twenty-four hours a day any ideas they might have about reality were sketchy at best. He understood that it was wrong but what could he do? She was his mother and while he tried to resist her, in the end he accepted her behavior as his own, even though officially he still disagreed with the lies.

When he was seventeen he either left her, or was kicked out of the house. There were two versions of this coming of age, but the one which most people recognize as true, and which was posted on his Wikipedia site, said that his mother had been living with two Mexican brothers near the border in Arizona and that her lovers had convinced her to give him the boot. Many saw this as the inspiration for one of his more scandalous and critically acclaimed pieces “Non scopare quei uomini Mama! (Don’t fuck those men, Mother)” This seminal work finishes tragically for the protagonist who is not only spurned by his mother, but also killed and barbecued by a group of famished Chicanos.

Moving to New York he financed his studies and living expenses selling LSD and pimping himself to wealthy lawyers and stockbrokers. It was a period that he looked back upon with a certain nostalgia and he could talk enthusiastically for hours about all the writers and musicians he knew or the time when he and a group of friends had hitchhiked up to Woodstock to see the concert.

He had lived through a lot and to be honest he thought that there wasn’t much that he hadn’t experienced that was worth knowing. He was a great artist and had been a part of the golden age in avant-garde theater of the 1980s and 90s. Of course, now that all of that had come to an inglorious end he realized that he needed to quickly write a book (and secure a movie deal) about his life. For this reason he was in near constant contact with his agent.

With a book, but especially with a movie deal, he wouldn’t have to worry about the unpaid bills that had kept him awake at night or the consistently bad reviews that his latest works had garnered or even sticking with his girlfriend. Daniela was pretty, and gifted in a commercial/pop/soap-opera kind of way, but he absolutely needed to avoid becoming any more dependent upon her than he already was. Just last night when they were eating at one of his favorite steak houses near the beach she’d asked him again if he really loved her and when he said that he did she upped the ante with “Well, don’t you think it’s time then that we got married?”

“What?!” he managed to blurt out as he almost choked on an exquisite piece of aged New York sirloin.

“Don’t you think it’s time?” she repeated with a knowing smile on her lips that he would have found attractive on any other woman but that on her filled him with a sense of panic and dread.

“I think there’s time for everything,” he told her after he’d swallowed his meat, “but we’ve only been together, for what?, three years? Why rush it? I love you and you love me and we’re fairly clear on that and there really isn’t any reason that I can see to over-emphasize this issue.”

“Then you don’t love me?”

“Not at all.” He said (which was the truth).

“What??”

“I mean that we shouldn’t jump into to this.”

“But I want to jump in, Gianni, and I want you to jump in with me.” And he knew that he was not going to get out of this one easily and in fact just about everything he said to her that night as they ate was not what she wanted to hear. It was as if his genius for spin and molding the truth of anything to his needs had abandoned him and all he could do was state, in as many different ways, that fundamentally he wasn’t all that fond of Daniela. Of course, he didn’t say that, but he wasn’t telling her what he knew she wanted to hear and this inability to lie troubled him. He wasn’t sure but he suspected that the combined stress of his financial and artistic situations was inhibiting his manipulative gifts and that if he didn’t find some kind of relief there was no telling where it might lead.

Fortunately, not all was wrong with his world. America had a new president and everything about the man was inspirational and led him to believe that change was indeed possible. An Afro-American in the White House had altered the political and social landscape of his country and he felt a special kinship to this politician in part because of his mother’s tale of his black, G.I. dad and in part because of the baby boy he’d secretly fathered with a woman from Harlem. In many ways, he’d come full circle and had, before anyone else knew about Obama, created his own personalized version of the man; a “mini-me” who embodied the best of the U.S. (racially speaking) and who, like his father, would some day see the necessity of alien relocation and language integrity.

“And if he doesn’t want to throw the Spics into the sea then he’s no son of mine.” He reminded himself as he skipped a flat rock into the Gulf Stream.

The illegals were a pestilence on the land. This was obvious to him. They were a diseased and unsanitary army that needed a good kicking in the butt. Having sucked greedily and for years at the nation’s vital juices they were sapping America of its strength and will to survive. Of course, as a patriot, and an artist, he knew what he had to do. He was way ahead of the curve and was just waiting for the movie deal to gel and take its final form.

“But shouldn’t he be calling me instead of me always having to call him?” he wondered. The man had an apartment in Manhattan but he was never there. In fact, Mentiroso couldn’t remember the last time that the two of them were physically together. They kept in touch text messaging and with quick conversations that the agent managed to squeeze in on his way to see other clients in LA or London.

The phone rang and rang and Mentiroso grew impatient. He paced back and forth with his Blackberry in the sand. The sun was coming up over the horizon and the sky in the distance had shades of lavender and light blue. There were three container ships steaming towards the port and seagulls kept watch atop the concrete pilings of a pier.

“Where the fuck is he?” said Mentiroso. “15% of everything I make goes to this clown and so, goddamnit, when I call he’s suppose to pick up the fracking phone.” But there was no answer. He obviously wasn’t on the agent’s list of priority clients.

A few hours later when he was sitting by himself at the hotel bar his agent finally acknowledged his existence with a short text message that read: “Gianni, no film deals with Warner/Universal. Try Disney?? Baci, Bernie.”

It certainly wasn’t what he wanted to hear but he had to admit that there were reasons. Not only was his agent incompetent, the studios were even worse. He felt surrounded by a sea of philistines and degenerates. No one could understand his art. It was beyond them. They were like ants, tiny little insignificant specs of societal sewage and frankly he had had enough of trying to educate them, of getting them to the point where they could see what he had always known.

“To hell with them,” he said as he downed his fourth shot of Grappa and ordered another. The bar had TVs set up in every corner and looking at the one in front of him there was a pudgy, balding journalist who in a deep, booming sort of voice was asking America again how much longer it could afford to support the illegal aliens in its midst.

“Damn right!” said Mentiroso. There were a few other people in the bar, but no one seemed to pay him any attention. The journalist was commenting on the latest I.C.E raid in Ohio. Immigration officers had surrounded a textile factory, shutting it down and arresting anyone who couldn’t prove their US citizenship. The operation was massive and well planned, targeting the thriving Latino community that for the most part worked in the factory.

As news of the raid spread throughout the community panicky parents rushed to pull their children out of the local school and hide them from the government agents. The journalist noted with a mix of solemnity and badly cloaked glee that over 200 illegal aliens had been apprehended and were at this very moment being processed for deportation.

“This,” he assured his audience, “is what I would call a good example of how our tax money should be spent and how it rarely ever is. A fresh start for America.”

“Indeed!” said Mentiroso as the bartender brought him his fifth round. He was pissed off at his agent and his mother, tired and somewhat disgusted with his girlfriend but more than anything else he felt positively sick at the thought of what the illegals were doing to America. He wanted them out and was ready to take whatever action was needed. After five shots of Grappa he was furious and had come to the conclusion that they were at the root of everything that was destroying his career. The journalist was right, better to deal with the problem before it got out of hand.

“Gimme a drink!” he said and the bartender handed him another shot. The pudgy-faced man was wrapping up his philippic and reminding Mentiroso that enforcing the law of the land was nothing to be ashamed of.

“I get plenty of emails accusing me of being anti-immigrant,” said the journalist, “but nothing could be further from the truth. All I want is for the laws of this great country of ours to be respected! And I ask you, is that too much to expect? Have we given up on the idea of America, on the idea of a land where Freedom, Justice and Liberty for all still mean something? I say not. The constitution still holds and anyone, and I mean women and children included, who enter this country illegally have to and will be forcefully removed, if necessary!”

“That’s the way you do it!” agreed Mentiroso. The shear stress of having to deal with these illegals was killing America’s mojo. It prevented the country from spinning its image abroad. It had conquered a world with its vision of wealth and individualism. It was sexy and cinematographic and casting his gaze about the bar he wondered if anyone else was as enthusiastic as he was about the immigration raid. There was a businessman near the entrance who was talking to a client on his cell phone, a couple in the corner holding hands and a group of young Cubans who pretended not to see him when he looked their way.

Not in a mood to be ignored he suddenly stood up and shouted in their direction “Tu puta madre (your mother’s a whore)!” He didn’t really speak Spanish but he knew enough to know that this was a bad insult.

“You talking to me, old man?” one of Cubans asked.

“Yeah, I’m talking to you!”

“Sit down, viejo, y cállate (shut up).”

“Stuff it, spics!” said Mentiroso and at that point even the businessman put down his phone. This was Miami after all and everyone in that room was Latino. The bartender came around to where Mentiroso was standing and calmly told him that it was time to take a deep breath and then leave. It was the sensible thing to do and in retrospect not only would it have saved him a lot of grief but his two front teeth as well. Instead, taking aim for the first time in his life, he threw his shot glass at the Cuban, hitting him squarely in the face. The reaction of the victim was immediate and soon he and his friends were pummeling Mentiroso. They were enraged and Mentiroso didn’t do anything to lessen their anger continuing as he did to insult their mothers, their girlfriends and whoever else he could think of. The more they beat him, in fact, the more he spewed out his stream of venom and race-hatred. His face had turned puffy and blue under their blows, his glasses were shattered, but he didn’t care. He was finally fighting the good fight, sacrificing himself for his art and his country on the altar of his many lies.

The bartender tried to pull him out but the Cubans wouldn’t stop. They wanted him dead, but before he passed out he reminded his assailants of one last thing: “I’m in charge,’ he said, “and that’s the truth.”

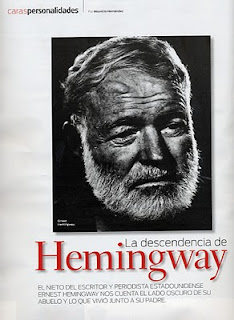

John Hemingway Copyright 2010, John Hemingway